Robert E. Lee was a great American. He was in rebellion against his country for four tortuous, bloody years. At the head of the Army of Northern Virginia, he came darn close to winning Southern independence. Lee was a brilliant field commander, full of audacity. His daring was a gift and a bane. He was a man of integrity. He was a man of his place and time. He deserves our remembrance and respect.

Robert E. Lee was a great American. He was in rebellion against his country for four tortuous, bloody years. At the head of the Army of Northern Virginia, he came darn close to winning Southern independence. Lee was a brilliant field commander, full of audacity. His daring was a gift and a bane. He was a man of integrity. He was a man of his place and time. He deserves our remembrance and respect.

The left – and the mainstream media, the Democratic Party, the race industry, and establishment go-alongs – want to destroy our history. Destroy anything that honors the men who fought for the South in the Civil War. Destroy, as the left does – here and abroad – history that doesn’t comport with its worldview. Destroy it or ignore it and rewrite it, as the Stalinists did. As Orwell warned.

That’s a villainous mindset. It contains an awfully destructive logic if not defeated. The left won’t stop at discarding the soldiers of the South’s rebellion. It will advance to anything and anyone the left deems inconvenient to its narrative – a narrative it fashions to gain power and control over all of us. If successful, the left will turn with a terrible vengeance on our founders. It will eviscerate the nation’s leaders in the generations up to the Civil War, and then beyond. It’s a means to tyranny.

Goes the left’s argument: the South’s secession was to preserve an evil institution, slavery – negro slavery, precisely. In large part, it was. But we live in dumbed down times, when schools fail to teach, or foist revisionist history on our kids; when history is barely remembered, much less understood; when tens of millions of citizens are open to falsehood, misrepresentation, and certainly lack of context about the momentous events and times and people in the past who shaped our nation.

Robert E. Lee was intimately connected to the nation’s beginnings. From Biography:

Lee was cut from Virginia aristocracy. His extended family members included a president, a chief justice of the United States, and signers of the Declaration of Independence. His father, Colonel Henry Lee, also known as “Light-Horse Harry,” had served as a cavalry leader during the Revolutionary War and gone on to become one of the war’s heroes, winning praise from General George Washington.

Lee married Mary Custis, whose great grandparents were George and Martha Washington. He graduated from West Point and distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War. In the small postwar army, Lee rose to the rank of colonel. He served as superintendent of the United States Military Academy.

Harper’s Ferry

Lee’s star rose when he was ordered to quell John Brown’s rebellion at Harper’s Ferry. He was then regarded as a possible leader of the Union army should civil war come.

When the war came, Lincoln offered Lee command of Union forces. Lee declined. It’s important to understand why – and it wasn’t because Lee was pro-slavery. Like most every American, he was, first and foremost, a citizen of his state: Virginia. When Virginia seceded, Lee acted from conviction: his duty lay with his state.

Modern Americans often travel across state lines. They relocate for work or lifestyle. They fail to appreciate mid-19th-century life. Though change was coming, Americans were still overwhelmingly rural, rarely venturing more than a dozen miles from their villages or farms. The nation was only loosely knitted together through the Revolution, rudimentary media, religion, and culture. The Civil War commenced just 72 years after Washington was sworn in as president.

Slavery had been contentious from the time the Constitution was debated and drafted. It remained contentious, in ebbs and flows, throughout the early decades of the republic. The 1850s saw an escalation in tensions and conflict about the issue. Lincoln’s election in 1860 proved the deal-breaker for 11 lower Southern states.

Most Southerners didn’t own slaves. They couldn’t afford them even if they desired to do so.

Lee didn’t believe in slavery. From a letter dated December 27, 1856:

There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race.

But, current with some thinking at the time, Lee wrote:

While my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter [blacks], my sympathies are more deeply engaged for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things.

Most assuredly, slavery was a “moral and political evil.” Yet Lee’s rationalization that blacks would progress to emancipation after an undefined period as slaves was in broad circulation among “enlightened” Southerners. Lee was a man of the South, a Virginian with social status. Racism was prevalent throughout the nation. Lee’s thinking was deemed progressive. The temptation is to impose early 21st-century sensibilities on Lee, whose correspondence is 161 years ancient.

The North and South were diverging. The former was industrializing, while the latter remained agrarian. The North’s demographics were changing, with influxes of European immigrants. The North had started to urbanize.

Fort Sumter

Lee, like many Southerners, fought for independence, not slavery. Those Southerners fought Northern tyranny – so perceived, though erroneous. Had it been a divorce, the South would have filed on grounds of irreconcilable differences. South Carolinians fired on Fort Sumter because they mistrusted Lincoln. They chose not to take him at his word. Reasoned Lincoln: No expansion of slavery, but leave the institution alone where it existed. Lincoln didn’t share Lee’s view of slavery as civilizing. He did believe that, in time, it would wither away. Nowadays, does that make Lincoln an abettor of slavery?

Lee, the gifted tactician, fought battle after battle against the superior Union army – outmanned, outgunned, out-provisioned. Lee profited from facing incompetent and feckless Union generals. Yet his boldness and talent for maneuver were decisive. Chancellorsville was, perhaps, his greatest victory. His aim to break the North’s will ran afoul of Gettysburg, which became his great defeat. U.S. Grant’s advent changed the dynamic. Grant used superior forces to doggedly pursue Lee, battering Lee’s army, cutting supply lines – finally surrounding him near Appomattox.

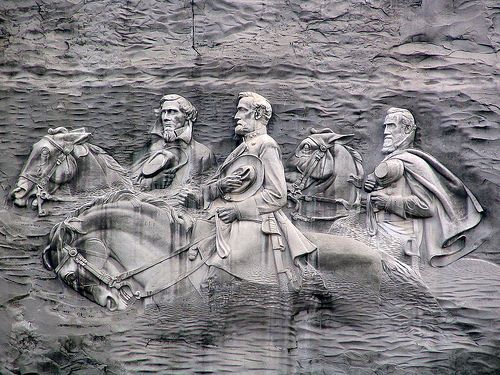

Sculpted figures of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson ~ Stone Mountain, Georgia

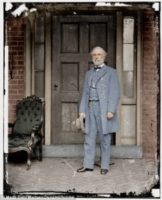

But Lee might have escaped Grant’s grip with a remnant of his troops, retreating to the Appalachians, vowing open-ended war, there inspiring or spawning thousands of William Quantrills and Bloody Bill Andersons. Instead, he surrendered, with no ironclad assurance that he’d not have a date with a hangman’s noose. Lee’s surrender and peaceful return to Richmond ended the Civil War.

The South wouldn’t reintegrate with the nation for another century. There would be decades of Southern apartheid (Jim Crow), KKK night ridings, lynchings of blacks – aided and abetted, if not orchestrated, by the Democratic Party. The Civil Rights Movement and laws closed that horrible chapter.

But the man, Robert E. Lee, must be remembered for the man. His sense of duty and loyalty to principle are unimpeachable. He must be seen and regarded in context: a man of achievement in a unique place and moment in time. Respect Lee; revile slavery.

The Civil War greatly shaped our nation. It’s intrinsic to our history, our reality. It has a truth – terrible, tragic, noble. Leftist revisionists be damned.

Written by J. Robert Smith for American Thinker ~ August 20, 2017

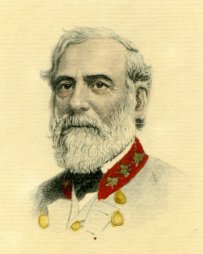

Gen. Robert E. Lee

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml