~ Overview ~

President Adams fully supported The Tariff of Abominations; designed to provide protection for New England manufacturers. The tariff was opposed, however, by supporters of Jackson. The Tariff of 1828, which included very high duties on raw materials, raised the average tariff to 45 percent. The Mid-Atlantic states were the biggest supporters of the new tariff. Southerners, on the other hand, who imported all of their industrial products, strongly opposed this tariff. They named the tariff “The Black Tariff” or “Tariff of Abominations.” They blamed this tariff for their worsening economic conditions.

Henry Clay

From the early days of the United States there was support to place tariffs (taxes on imported goods) to help new American industries to effectively compete. After the War of 1812, the British were able to flood the American markets with cheaper goods. Support grew to increase tariffs. Leading that charge to increase tarriffs was Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay believed in an American system of trade; a system where American manufacturers were protected and allowed to grow, while the income from the tariffs would be used for internal improvements. Clay also wanted to insure that the US would not be dependent on the British. The rising quantity of manufacturing in the North converted some New Englanders, including Daniel Webster, who had supported free trade, to become supporters of a rise in tariffs.

In 1816, in the aftermath of the war, the Congress passed another tariff Act that levied a Tariff of 25% on many imported goods. While this represented a rise, it was not considered very high for the times. The Panic of 1819, largely caused by the worldwide drop in the commodity prices, encouraged many in Congress to try to wall the US off, as much as possible, from the vagaries of the world wide markets. In 1820 a more protective measure passed the House, but failed to pass the Senate, due to Southern opposition. The South, however, was fighting a losing battle. The North continued to develop industry rapidly, while the South relied more and more on growing and selling cotton.

The population of the North continued to expand. More importantly, in the battle over the tariffs, the western states that were being added to the Union tended to favor stronger tariffs. Finally, in 1824, with Henry Clay in the powerful position of Speaker of the House, tariffs were raised to 35 percent on imported iron, wool and hemp. Many supporters of tariffs thought that 35 percent was not high enough. There were many tariff supporters who wanted to raise the tariffs even higher. Supporters of soon to be President Jackson devised a plan to increase tariffs in a way to help the Mid Atlantic states, states that would be crucial to Jacksons election hopes. They did this, despite the clear opposition of Southern states, led by Senator Calhoun. Supporters of a tariff rise were victorious and some tariffs were increased to as much as 50%. ~ Ed.

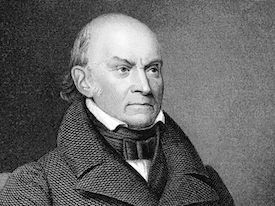

John Quincy Adams

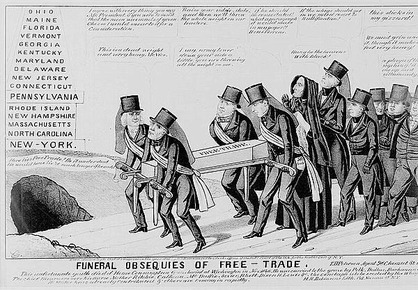

Tariff of Abominations

The Tariff of 1828 was a protective tariff passed by the Congress of the United States on May 19, 1828, designed to protect industry in the Northern United States. Created during the presidency of John Quincy Adams and enacted during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, it was labeled the “Tariff of Abominations” by its Southern detractors because of the effects it had on the Southern economy. It set a 38% tax on some imported goods and a 45% tax on certain imported raw materials. The manufacturing-based economy in the Northern United States was suffering from low-priced imported goods from Europe. The major goal of the tariff was to protect the North’s industries by taxing goods from Europe. Some in the South, particularly those from South Carolina, felt they were harmed directly by having to pay more for goods imported from Europe. Possibly, the South was also harmed indirectly because reducing the exportation of British goods to the U.S. would make it difficult for the British to pay for the cotton they imported from the South. The reaction in the South, particularly in South Carolina, led to the Nullification Crisis. The tariff marked the high point of U.S. tariffs in terms of average percent of value taxed, though not resulting revenue as percent of GDP.

Passage of the Bill

The 1828 tariff was part of a series of tariffs that began after the War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars, when the blockade of Europe led British manufacturers to offer goods in America at low prices that American manufacturers often could not match. The first protective tariff was passed by Congress in 1816; its tariff rates were increased in 1824. Southern states such as South Carolina contended that the tariff was unconstitutional and were opposed to the newer protectionist tariffs, as they would have to pay, but Northern states favored them because they helped strengthen their industrial-based economy.

President Andrew Jackson

In an elaborate scheme to prevent passage of still higher tariffs, while at the same time appealing to Andrew Jackson‘s supporters in the North, John C. Calhoun and other Southerners joined them in crafting a tariff bill that would also weigh heavily on materials imported by the New England states. It was believed that President John Quincy Adams‘s supporters in New England, the National Republicans, or as they would later be called, Whigs, would uniformly oppose the bill for this reason and that the Southern legislators could then withdraw their support, killing the legislation while blaming it on New England.

What that plan was, Calhoun explained very frankly nine years later, in a speech reviewing the events of 1828 and defending the course taken by himself and his southern fellow members. A high-tariff bill was to be laid before the House. It was to contain not only a high general range of duties, but duties especially high on those raw materials on which New England wanted the duties to be low. It was to satisfy the protective demands of the Western and Middle States, and at the same time to be obnoxious to the New England members. The Jackson men of all shades, the protectionists from the North and the free-traders from the South, were to unite in preventing any amendments; that bill, and no other, was to be voted on. When the final vote came, the Southern men were to turn around and vote against their own measure. The New England men, and the Adams men in general, would be unable to swallow it, and would also vote against it. Combined, they would prevent its passage, even though the Jackson men from the North voted for it. The result expected was that no tariff bill at all would be passed during the session, which was the object of the Southern wing of the opposition. On the other hand, the obloquy of defeating it would be cast on the Adams party, which was the object of the Jacksonians of the North. The tariff bill would be defeated, and yet the Jackson men would be able to parade as the true “friends”.

Southern opponents generally felt that the protective features of tariffs were harmful to Southern agrarian interests and claimed they were unconstitutional because they favored one sector of the economy over another. New England importers and ship owners also had reason to oppose provisions targeting their industries—provisions inserted by Democratic Party legislators to induce New England constituents to sink the legislation.

Those in Western states and manufacturers in the Mid-Atlantic States argued that the strengthening of the nation was in the interest of the entire country. This same reasoning swayed two-fifths of U.S. Representatives in the New England states to vote for the tariff increase. In 1824, New England was on the verge of bankruptcy due to the influx of the use of European cloth. New England was in favor of the tariff increase for entering goods from Europe to aid in the country’s economic success.

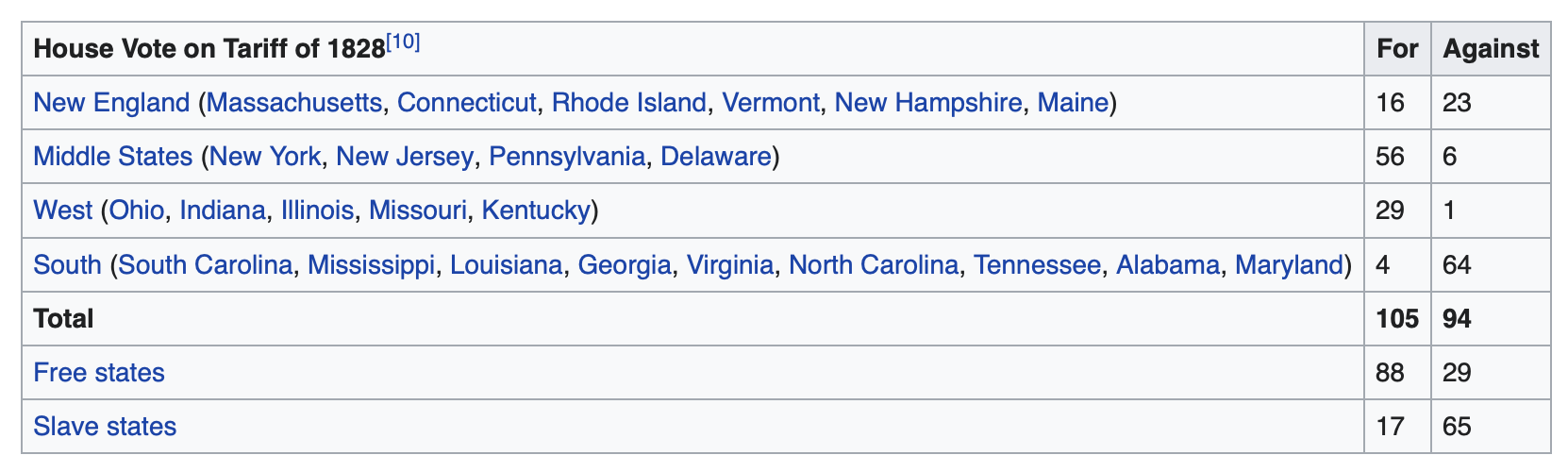

A substantial minority of New England Congressmen (41%) saw what they believed to be long-term national benefits of an increased tariff, and voted for it; they believed the tariff would strengthen the manufacturing industry nationally (see table).

The Democratic Party had miscalculated: despite the insertion by Democrats of import duties calculated to be unpalatable to New England industries, most specifically on raw wool imports, essential to the wool textile industry, the New Englanders failed to sink the legislation, and the Southerners’ plan backfired.

The 1828 tariff was signed by President Adams, although he realized it could weaken him politically. In the presidential election of 1828, Andrew Jackson defeated Adams with a popular tally of 642,553 votes and an electoral count of 178 as opposed to Adams’s 500,897 tally and 83 electoral votes.

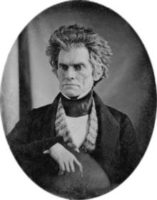

John C. Calhoun

Effects of the tariff

Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina strongly opposed the tariff, anonymously authoring a pamphlet in December 1828 titled the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, in which he urged nullification of the tariff within South Carolina. The South Carolina legislature, although it printed and distributed 5,000 copies of the pamphlet, took none of the legislative action that the pamphlet urged.

The expectation of the tariff’s opponents was that with the election of Jackson in 1828, the tariff would be significantly reduced. When the Jackson administration failed to address its concerns, the most radical faction in South Carolina began to advocate that the state itself declare the tariff null and void within South Carolina.[citation needed]

In Washington, an open split on the issue occurred between Jackson and Vice-President Calhoun. On July 14, 1832, Jackson signed into law the Tariff of 1832 which made some reductions in tariff rates.[citation needed] Calhoun resigned on December 28 of the same year.

The reductions were too little for South Carolina. In November 1832 the state called for a convention. By a vote of 136 to 26, the convention overwhelmingly adopted an ordinance of nullification drawn by Chancellor William Harper. It declared that the tariffs of both 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and unenforceable in South Carolina. While the Nullification Crisis would be resolved with a compromise known as the Tariff of 1833, tariff policy would continue to be a national political issue between the Democratic Party and the newly emerged Whig Party for the next twenty years

The above has been compiled from a series of different sources. ~ Ed.