In December of 1860, many Republicans were beginning to take the secession movement seriously and felt that a compromise needed to be reached in order to keep the Upper South, including states like North Carolina and Tennessee, from seceding. For this reason, two committees were convened by Congress for the express purpose of dealing with proposals aimed at averting the secession crisis. The House of Representative’s “Committee of Thirty-Three” was formed on 4 December, 1860, the day after the second session of the thirty-sixth Congress convened. This committee took its name from the thirty-three Representatives, one from each state, that were appointed to its seats. The committee, chaired by Thomas Corwin of Ohio, met for the first time on 11 December. The Senate’s “Committee of Thirteen” was created on 18 December, and like the Committee of Thirty-Three, took its name from the number of seats assigned to it. On 20 December, Vice-President John C. Breckinridge appointed thirteen Senators to the committee, and they met for the first time that very day.

In December of 1860, many Republicans were beginning to take the secession movement seriously and felt that a compromise needed to be reached in order to keep the Upper South, including states like North Carolina and Tennessee, from seceding. For this reason, two committees were convened by Congress for the express purpose of dealing with proposals aimed at averting the secession crisis. The House of Representative’s “Committee of Thirty-Three” was formed on 4 December, 1860, the day after the second session of the thirty-sixth Congress convened. This committee took its name from the thirty-three Representatives, one from each state, that were appointed to its seats. The committee, chaired by Thomas Corwin of Ohio, met for the first time on 11 December. The Senate’s “Committee of Thirteen” was created on 18 December, and like the Committee of Thirty-Three, took its name from the number of seats assigned to it. On 20 December, Vice-President John C. Breckinridge appointed thirteen Senators to the committee, and they met for the first time that very day.

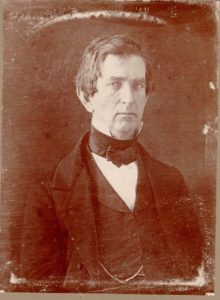

Several proposals for compromise were being considered by these committees, but little to no progress was being made. Then, on 24 December, 1860, Representative Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts introduced a new proposal to the Committee of Thirty-Three. That same day, the very same proposal was introduced to the Committee of Thirteen by Lincoln’s soon-to-be Secretary of State, Senator William H. Seward of New York, who, it turned out, had supplied Adams with the text of said proposal. That proposal also failed in both committees, but in time, would be put back on the table as a last-ditch attempt to solve the secession crisis.

Photo of Senator (later Secretary of State) William H. Seward (R, NY). Seward served on the Senate committee that was established to find a way to avert the secession crisis, and he introduced what would become the Corwin Amendment to the Senate.

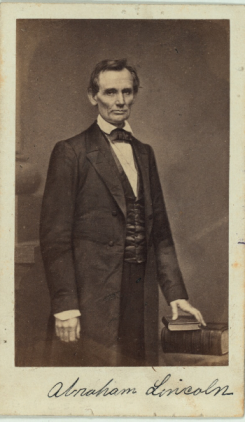

That particular proposal’s origins are historically uncertain, as is the manner by which Seward came to propose it, although a fairly decent amount of evidence points directly to Abraham Lincoln. Surviving correspondence confirms that the proposal was introduced following a conversation between Seward and Thurlow Weed, editor of the Albany Evening Journal and an operative for the Republican Party. President-elect Lincoln, in his December correspondence with William Seward, had remained resolute that there would be absolutely no compromises as far as the extension of slavery into the territories northwest of Missouri, and any as-of-yet non-existent states that may in the future seek admission to the Union. Then, on 20 December, 1860, Lincoln, who had been a political ally of Seward for quite some time, summoned Thurlow Weed to Springfield, Illinois, for a meeting to discuss the various compromise proposals being considered by Congress. In the course of that meeting, Lincoln provided Weed with several compromise proposals that he, Lincoln, had penned, to be forwarded to Seward.

After the meeting with Lincoln, Weed returned to New York bearing a memorandum from Lincoln to Seward that outlined Lincoln’s thoughts on the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause, although it had very little to say on the subject of constitutional protection of slavery. Weed also told Seward that Lincoln had “verbally” conveyed a suggestion “prepared for the consideration of the Republican members.” Seward, after receiving Lincoln’s proposals from Weed upon his return to New York, introduced three resolutions to the Senate’s Committee of Thirteen on 24 December. One of these was Lincoln’s “verbal” proposal, the very proposal that Seward had supplied Adams with the text to; the so-called “Corwin Amendment,” which took its name not from its Congressional sponsors, but from Representative Thomas Corwin, Chairman of the Committee of Thirty-Three.

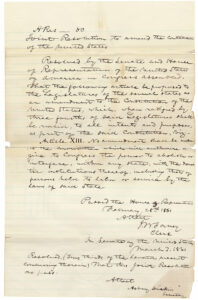

The Corwin Amendment was a proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. It read as follows: “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” If passed by the House and the Senate, and ratified by 21 states, or, if the already-seceded states were included, 26 states, the Thirteenth Amendment would not have abolished the institution of slavery in the United States, but would instead have made it ineradicable, except by the legislatures of the individual states.

In a letter dated 26 December, 1860, Seward informed Lincoln that Weed had indeed told him about Lincoln’s spoken-but-not-written suggestion “prepared for the consideration of the Republican members.” In the letter, Seward described Weed’s verbally relayed “suggestion” as a resolution stating that, “… the constitution should never be altered so as to authorize Congress to abolish or interfere with slavery in the state,” which begs the question, was Lincoln the unidentified co-author, if not the author himself, of the Corwin Amendment? Elsewhere in Lincoln’s papers is supportive evidence. Weed and Seward were not the only men to receive instructions from Lincoln.

On 21 December, the day after his meeting with Thurlow Weed, Lincoln notified Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois that he could expect to receive “three short resolutions which I drew up, and which, on the substance of which, I think would do much good.” On 27 December, or slightly before, Thurlow Weed presented the incoming Vice-President, Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, with Lincoln’s memorandum. In a letter to Lincoln, Hamlin’s description of the conversation with Weed communicates very little about the content of the memorandum relayed to Seward by Weed except to make mention of its existence. However, it does post-date Seward’s presentation of the Corwin Amendment to the Republican members of the Committee of Thirteen, revealing that Hamlin evidently believed that the proposed amendment was sanctioned by Lincoln.

On 21 December, the day after his meeting with Thurlow Weed, Lincoln notified Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois that he could expect to receive “three short resolutions which I drew up, and which, on the substance of which, I think would do much good.” On 27 December, or slightly before, Thurlow Weed presented the incoming Vice-President, Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, with Lincoln’s memorandum. In a letter to Lincoln, Hamlin’s description of the conversation with Weed communicates very little about the content of the memorandum relayed to Seward by Weed except to make mention of its existence. However, it does post-date Seward’s presentation of the Corwin Amendment to the Republican members of the Committee of Thirteen, revealing that Hamlin evidently believed that the proposed amendment was sanctioned by Lincoln.

On 28 December, 1860, Abraham Lincoln sent Senator Trumbull another letter which detailed a visit to Lincoln by one Duff Green, an agent of outgoing President James Buchanan, who was sent to Springfield on an unofficial mission to establish exactly how the President-Elect stood on the issue of secession and to attempt to get Lincoln to give a public statement about his feelings on the compromise proposals being considered by Congress. Lincoln was, to say the least, evasive in what he said to Green. Green had long been a Washington political operative, and had active lines of communication with those on both sides of the secession issue, so Lincoln would not answer his questions directly. Instead, he wrote a memorandum for Green which he forwarded to Senator Trumbull, with instructions to share the letter’s contents with Senators Seward and Hamlin. The three Senators were instructed to release the memorandum to the public only if it was believed it would give aid to their cause, but, Lincoln stipulated, before the memorandum could be released to the public, Green had to obtain the support of the Senators from the seceding states in writing. Lincoln’s memorandum of 28 December, the “Green Memorandum,” was abstract as far as his feelings about a constitutional amendment, his position being dependent upon the wishes of “the American People,” but also alluded to the fact that he would support a proposition such as Senator Seward’s proposed Corwin Amendment. He wrote, “I declare that the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively.” Lincoln made it known to Senator Trumbull that the statement was adapted “from the Chicago Platform” of the Republican Party, but that Green “need not” know this. Senators Trumbull, Seward, and Hamlin ultimately decided not to release the Green Memorandum to the public, although Trumbull privately told Green of its essence a few days later.

This tells us something of Lincoln’s views of the Corwin Amendment during December of 1860, when it was first introduced to the Congressional committees. The Corwin Amendment was introduced to both committees on 24 December. Senator Seward informed Lincoln of this in a letter on 26 December. That letter, Lincoln’s first notification that Seward had acted on the instructions forwarded to him by Thurlow Weed after his meeting with Lincoln on 20 December, had not yet found its way to Lincoln by the time he penned the Green Memorandum on 28 December. This is known because said letter’s postmark indicates it was processed at the Post Office in Washington, D.C. on 27 December. It is not possible for it to have arrived in Springfield, Illinois, by 28 December. The fact that the statement Lincoln made in the Green Memorandum practically mirrored the ideas contained in Senator Seward’s proposal of 24 December would suggest, very strongly indeed, that Lincoln and Seward were of like mind on the subject.

By the end of December, 1860, the two Congressional committees had reached an impasse. Two of the most favored proposals, the Crittenden Plan and the Washington Peace Convention, had been deemed as unacceptable by the Republicans because neither opposed the extension of slavery to new territories and states, and were felt to yield far too much to the slave states. As a result, the Corwin Amendment, as aforementioned, was put back on the table as the only viable solution to the secession crisis. For the next two months, it worked its way through Congress. Lincoln would make no public statement concerning the proposal until his first Inaugural Address on 4 March, 1861, although he would, after arriving in Washington, D.C. in late February, actively lobby for support of the amendment. Lieutenant General Winfred Scott, the hero of the Mexican-American War and Commanding General of the United States Army was of the belief that to win a war against the then-seven Confederate States would take three hundred thousand men two or three years of hard fighting, and two hundred fifty million dollars; nearly the same as the entire annual national budget. In light of the perceived cost, the Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, began lobbying even harder for support of the Corwin Amendment.

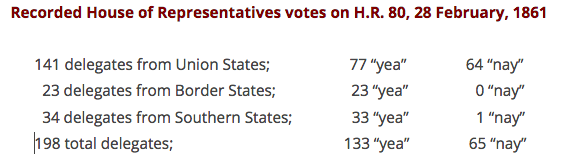

On 28 February, 1861, the House of Representatives, thirty-sixth United States Congress, 5 December, 1859 – 27 March, 1861, voted on the Corwin Amendment, proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, House Resolution 80, and passed it with a vote of one hundred and thirty-three to sixty-five. The recorded votes of the House are as follows:

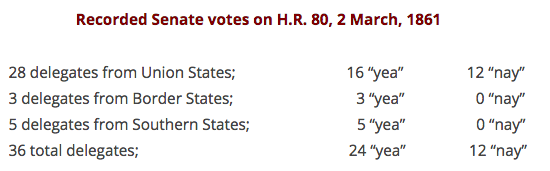

Lobbying continued, as did discussion in the Senate, and on 2 March, 1861, the United States Senate, thirty-sixth United States Congress, 5 December, 1859 – 27 March, 1861, voted on the Corwin Amendment, proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, House Resolution 80, and passed it with a vote of twenty-four to twelve. The recorded votes of the Senate are as follows:

Lobbying continued, as did discussion in the Senate, and on 2 March, 1861, the United States Senate, thirty-sixth United States Congress, 5 December, 1859 – 27 March, 1861, voted on the Corwin Amendment, proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, House Resolution 80, and passed it with a vote of twenty-four to twelve. The recorded votes of the Senate are as follows:

It was signed on by President James Buchanan that same day, and the amendment was sent to the State Legislatures for ratification. Henry Adams, son of the Corwin Amendment’s co-sponsor, Representative Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts, and a clerk in his father’s office, would later say that the amendment passed only because of “some careful manipulation, as well as the direct influence of the new President.”

It was signed on by President James Buchanan that same day, and the amendment was sent to the State Legislatures for ratification. Henry Adams, son of the Corwin Amendment’s co-sponsor, Representative Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts, and a clerk in his father’s office, would later say that the amendment passed only because of “some careful manipulation, as well as the direct influence of the new President.”

On 4 March, 1861, in his first Inaugural Address, Lincoln said of the Corwin Amendment, “I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution [the Corwin Amendment] – which amendment, however, I have not seen – has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service. To avoid misconstruction of what I have said, I depart from my purpose not to speak of particular amendments so far as to say that, holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.” It was Lincoln’s hope that by lending his tacit support to the Corwin Amendment, he could convince the Slave States that he had no intention of abolishing slavery and thereby possibly prevent the secession of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, and Texas.

On 16 March, 1861, Lincoln sent a form letter, a copy of which can be found at the Lehigh County Historical Society in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to each of the states’ governors, including those of the states that had already seceded, conveying “an authenticated copy of a Joint Resolution to amend the Constitution of the United States.” The amendment spoken of was without a doubt the Corwin Amendment, as no other constitutional amendments were being considered at that time, and the letter was the first step to the ratification of the amendment by the states. Kentucky ratified the Corwin Amendment on 4 April, 1861, and eight days later the Confederate batteries around Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, opened fire on Fort Sumter. By the time Ohio ratified the amendment on 13 May, 1861, Virginia and Arkansas had seceded in the wake of Lincoln’s call for troops. Rhode Island ratified the amendment on 31 May, by which time North Carolina had seceded. Texas would secede eight days later. The Corwin Amendment, which had failed to prevent the secession of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Texas went on to be ratified by Maryland on 10 January, 1862. The fifty counties in Northwestern Virginia, which would eventually become the state of West Virginia, ratified the amendment on 13 February, 1862, and Illinois ratified it the next day. By the time the Corwin Amendment was ratified by Illinois, the War had become the main focus of all the states, North and South, and the ratification process stalled. Had the War not caused the process of ratification to stall, the Corwin Amendment would very likely have been ratified by the required three-quarters of the states and become the Thirteenth Amendment, forever enshrining the institution of slavery in the United States, because twenty-seven of the thirty-six states, not including the territory of Utah and Washington, D.C. were Slave States. If the territory of Utah and Washington, D.C. had been included, the number of Slave States/Territories would have been twenty-nine.

The Corwin Amendment was a very real and serious attempt to forever constitutionally protect the institution of slavery in the United States, and like it or not, Abraham Lincoln, the “Great Emancipator,” not only had a hand in its creation, but may have been solely responsible for it. He also played a key role in its adoption by Congress. These facts, in and of themselves, shed a very different light on the character of the man. Lincoln did not care whether slavery was abolished or not, he only cared about avoiding secession, and possibly war, so that taxes could be collected from the Southern States; but that is another story. The fact remains that the man renowned for “freeing the slaves” actually did his best to make slavery a permanent institution in the United States, and he almost succeeded. His later moves on the political chessboard, such as the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, do not, and cannot, change that fact.

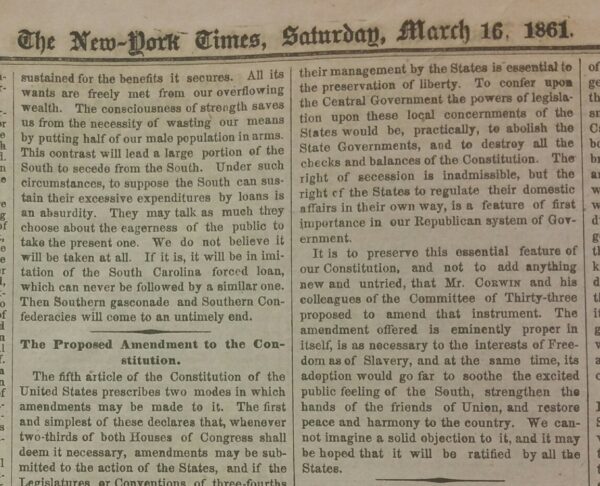

The Corwin Amendment, New York Times, March 3, 1861

~ Final Notes on the Corwin Amendment ~

Although the ratification process was stalled by the War, the amendment itself is not actually dead; it merely lies dormant to this very day. Its passage by the House of Representatives and the Senate is constitutional fact, and as such, is irreversible. Even though Ohio rescinded its ratification on 31 March, 1864, and Maryland did likewise on 7 April, 2014, if thirty-four more states, or thirty-five if you take into account the fact that some dispute its ratification by Illinois because it was ratified by the Illinois Constitutional Convention instead of the State Legislature, because the Convention was the only representative body officially functioning in the state at the time, it could present a very serious constitutional crisis. It would create a genuine question of constitutional law as to whether or not it would overrule the current Thirteenth Amendment, as it was adopted by the United States Congress first. Of course, the possibility of such a thing actually happening is much too far from the realm of reality to be taken seriously, but the theoretical possibility does exist…

October 12, 2017

K. Lance Spivey

Deo Vindice…

Pingback: The Script for a 200 Year Long Soap Opera: How It All Unraveled | Metropolis.Café