Noah Webster

Another defect in our schools, which, since the revolution, is become inexcuseable, is the want of proper books. The collections which are now used consist of essays that respect foreign and ancient nations. The minds of youth are perpetually led to the history of Greece and Rome or to Great Britain; boys are constantly repeating the declamations of Demosthenes and Cicero, or debates upon some political question in the British Parliment. These are excellent specimens of good sense, polished stile and perfect oratory; but they are not interesting to children. They cannot be very useful, except to young gentlemen who want them as models of reasoning and eloquence, in the pulpit or at the bar.

But every child in America should be acquainted with his own country. He should read books that furnish him with ideas that will be useful to him in life and practice. As soon as he opens his lips, he should rehearse the history of his own country; he should lisp the praise of liberty, and of those illustrious heroes and statesmen, who have wrought a revolution in her favor.

A selection of essays, respecting the settlement and geography of America; the history of the late revolution and of the most remarkable characters and events that distinguished it, and a compendium of the principles of the federal and provincial governments, should be the principal school book in the United States. These are interesting objects to every man; they call home the minds of youth and fix them upon the interests of their own country, and they assist in forming attachments to it, as well as in enlarging the understanding.

“It is observed by the great Montesquieu, that the laws of education ought to be relative to the principles of the government.”

In despotic governments, the people should have little or no education, except what tends to inspire them with a servile fear. Information is fatal to despotism.

In monarchies, education should be partial, and adapted to the rank of each class of citizens. But “in a republican government,” says the same writer, “the whole power of education is required.” Here every class of people should know and love the laws. This knowlege should be diffused by means of schools and newspapers; and an attachment to the laws may be formed by early impressions upon the mind.

Two regulations are essential to the continuance of republican goverments: 1. Such a distribution of lands and such principles of descent and alienation, as shall give every citizen a power of acquiring what his industry merits.1 2. Such a system of education as gives every citizen an opportunity of acquiring knowlege and fitting himself for places of trust. These are fundamental articles; the sine qua non of the existence of the American republics.

Two regulations are essential to the continuance of republican goverments: 1. Such a distribution of lands and such principles of descent and alienation, as shall give every citizen a power of acquiring what his industry merits.1 2. Such a system of education as gives every citizen an opportunity of acquiring knowlege and fitting himself for places of trust. These are fundamental articles; the sine qua non of the existence of the American republics.

Hence the absurdity of our copying the manners and adopting the institutions of Monarchies.

In several States, we find laws passed, establishing provision for colleges and academies, where people of property may educate their sons; but no provision is made for instructing the poorer rank of people, even in reading and writing. Yet in these same States, every citizen who is worth a few shillings annually, is entitled to vote for legislators.2 This appears to me a most glaring solecism in government. The constitutions are republican, and the laws of education are monarchical. The former extend civil rights to every honest industrious man; the latter deprive a large proportion of the citizens of a most valuable privilege.

In our American republics, where [government] is in the hands of the people, knowlege should be universally diffused by means of public schools. Of such consequence is it to society, that the people who make laws, should be well informed, that I conceive no Legislature can be justified in neglecting proper establishments for this purpose.

When I speak of a diffusion of knowlege, I do not mean merely a knowlege of spelling books, and the New Testament. An acquaintance with ethics, and with the general principles of law, commerce, money and government, is necessary for the yeomanry of a republican state. This acquaintance they might obtain by means of books calculated for schools, and read by the children, during the winter months, and by the circulation of public papers.

“In Rome it was the common exercise of boys at school, to learn the laws of the twelve tables by heart, as they did their poets and classic authors.” What an excellent practice this in a free government!

It is said, indeed by many, that our common people are already too well informed. Strange paradox! The truth is, they have too much knowlege and spirit to resign their share in government, and are not sufficiently informed to govern themselves in all cases of difficulty.

There are some acts of the American legislatures which astonish men of information; and blunders in legislation are frequently ascribed to bad intentions. But if we examin the men who compose these legislatures, we shall find that wrong measures generally proceed from ignorance either in the men themselves, or in their constituents. They often mistake their own interest, because they do not foresee the remote consequences of a measure.

It may be true that all men cannot be legislators; but the more generally knowlege is diffused among the substantial yeomanry, the more perfect will be the laws of a republican state.

Every small district should be furnished with a school, at least four months in a year; when boys are not otherwise employed. This school should be kept by the most reputable and well informed man in the district. Here children should be taught the usual branches of learning; submission to superiors and to laws; the moral or social duties; the history and transactions of their own country; the principles of liberty and government. Here the rough manners of the wilderness should be softened, and the principles of virtue and good behaviour inculcated. The virtues of men are of more consequence to society than their abilities; and for this reason, the heart should be cultivated with more assiduity than the head.

Such a general system of education is neither impracticable nor difficult; and excepting the formation of a federal government that shall be efficient and permanent, it demands the first attention of American patriots. Until such a system shall be adopted and pursued; until the Statesman and Divine shall unite their efforts in forming the human mind, rather than in loping its excressences, after it has been neglected; until Legislators discover that the only way to make good citizens and subjects, is to nourish them from infancy; and until parents shall be convinced that the worst of men are not the proper teachers to make the best; mankind cannot know to what a degree of perfection society and government may be carried. America affords the fairest opportunities for making the experiment, and opens the most encouraging prospect of success.

1. The power of entailing real estates is repugnant to the spirit of our American governments.

2. I have known instructions from the inhabitants of a county, two thirds of whom could not write their names. How competent must such men be to decide an important point in legislation!

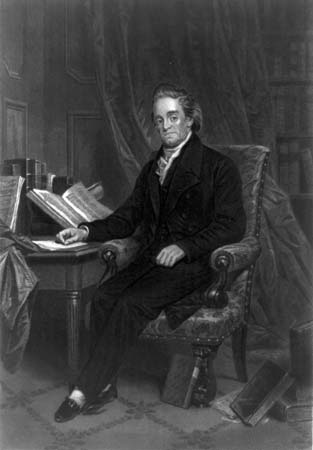

~ The Author ~

Noah Webster was born on October 16, 1758, in the West Division of Hartford. Noah’s was an average colonial family. His father farmed and worked as a weaver. His mother worked at home. Noah and his two brothers, Charles and Abraham, helped their father with the farm work. Noah’s sisters, Mercy and Jerusha, worked with their mother to keep house and to make food and clothing for the family.

Few people went to college, but Noah loved to learn so his parents let him go to Yale, Connecticut’s only college. He left for New Haven in 1774, when he was 16. Noah’s years at Yale coincided with the Revolutionary War. Because New Haven had food shortages during this time, many of Noah’s classes were held in Glastonbury.

Few people went to college, but Noah loved to learn so his parents let him go to Yale, Connecticut’s only college. He left for New Haven in 1774, when he was 16. Noah’s years at Yale coincided with the Revolutionary War. Because New Haven had food shortages during this time, many of Noah’s classes were held in Glastonbury.

Noah graduated in 1778. He wanted to study law, but his parents could not afford to give him more money for school. So, in order to earn a living, Noah taught school in Glastonbury, Hartford and West Hartford. Later he studied law. [Additional fact: in 1784 Connecticut started the first law school in America, which graduated Noah Webster]

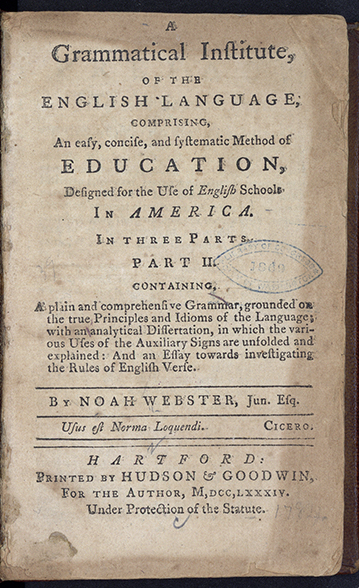

Noah did not like American schools. Sometimes 70 children of all ages were crammed into one-room schoolhouses with no desks, poor books, and untrained teachers. Their books came from England. Noah thought that Americans should learn from American books, so in 1783, Noah wrote his own textbook: A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. [Additional fact: In 1783 Noah also produced what is considered to be the first dictionary created in the US] Most people called it the “Blue-backed Speller” because of its blue cover.

For 100 years, Noah’s book taught children how to read, spell, and pronounce words. It was the most popular American book of its time. Ben Franklin used Noah’s book to teach his granddaughter to read.

When Noah was 43, he started writing the first American dictionary. He did this because Americans in different parts of the country spelled, pronounced and used words differently. He thought that all Americans should speak the same way. He also thought that Americans should not speak and spell just like the English.

Noah used American spellings like “color” instead of the English “colour” and “music” instead ” of “musick”. He also added American words that weren’t in English dictionaries like “skunk” and “squash”. It took him over 27 years to write his book. When finished in 1828, at the age of 70, Noah’s dictionary had 70,000 words in it.

Noah did many things in his life. He worked for copyright laws, wrote textbooks, Americanized the English language, and edited magazines. When Noah Webster died in 1843 he was considered an American hero.