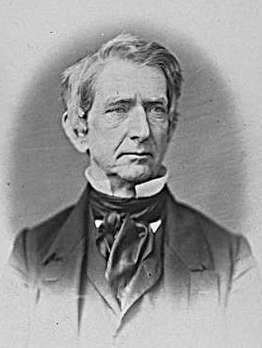

William Seward

ROCHESTER, N. Y., October 25, 1858 – Almost on the eve of this year’s momentous election, when slavery has become virtually the sole issue – and particularly the question of how Kansas and other prospective states are to be admitted into the Union – Senator William Henry Seward challenged here today the very integrity of the Democratic party and its espousal of slavery in those present or future states where it is legal.

The Senator is not a candidate for re-election, as his term has two more years to run. His prestige is so great, beginning with his governorship of this state in 1838 and continuing through a Senate career that began in 1849, that he might well have remained out of this contest. Nevertheless, he has taken such a forceful stand that he maybe counted in the forefront of the fight just as vigorously as, for instance, Mr. Abraham Lincoln, who in Illinois is staking his political future on a campaign for a Senate seat.

More remarkable, in Senator Seward’s case, is the fact that a delicate balance of political strength in New York finds the Democrats, who will put a candidate into the field against him two years hence, almost equally as strong as his own party, even though New York is permanently and irrevocably aligned with the “free states.”

Against that background, his speech is not only dramatic but also courageous.

The history of the Democratic Party commits it to the policy of slavery. It has been the Democratic party, and no other agency, which has, carried that policy up to its present alarming culmination. Without stop- ping to ascertain critically, the origin of the present Democratic party, we may concede its claim to date from the era of good feeling, which occurred under the administration of President Monroe. At that time, in this State, and about that time in many others of the free States, the Democratic party deliberately disfranchised the free colored or African citizen, and it has pertinaciously continued this disfranchisement ever since. This was an effective aid to slavery; for, while the slaveholder votes for his slaves against freedom, the freed slave in the free States is prohibited from voting against slavery. In 1824, the democracy resisted the election of John Quincy Adams – himself before that time an acceptable Democrat – and in 1828 it expelled him from the Presidency and put a slave-holder in his place, although the office had been filled by slave-holders thirty-two out of forty years.

In 1836, Martin Van Buren – the first non-slave-holding citizen of a free State to whose election the Democratic party ever consented – signalized his inauguration into the Presidency by a gratuitous announcement that under no circumstances, would he ever approve a bill for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. From 1838 to 1844 the subject of abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia and in the national dockyards and arsenals, was brought before Congress by repeated popular appeals. The Democratic party thereupon promptly denied the right of petition, and effectually suppressed the freedom of speech in Congress, so far as the institution of slavery was concerned.

From 1840 to 1843 good and wise men counselled that Texas should remain outside the Union until she should consent to relinquish her self-instituted slavery; but the Democratic party precipitated her admission into the Union, not only without that condition, but even with a covenant that the State might be divided and reorganized so as to constitute four slave States instead of one. In 1846, when the United States became involved in a war with Mexico, and it was apparent that the struggle would end in the dismemberment of that republic, which was a non-slave-holding power, the Democratic party rejected a declaration that slavery should not be established within the territory to be acquired. When, in 1850, governments were to be instituted in the territories of California and New Mexico, the fruits of that war, the Democratic party refused to admit New Mexico as a free State, and only consented to admit California as a free State on the condition, as it has since explained the transaction, of leaving all of New Mexico and Utah open to slavery, to which was also added the concession of perpetual slavery in the District of Columbia and the passage of an unconstitutional, cruel and humiliating law, for the recapture of fugitive slaves, with a further stipulation that the subject of slavery should never again be agitated in either chamber of Congress. When, in 1854, the slave-holders were contentedly reposing on these great advantages, then so recently won, the Democratic party unnecessarily, officiously, and with super-serviceable liberality, awakened them from their slumber, to offer and force on their acceptance the abrogation of the law which declared that neither slavery nor involuntary servitude should ever exist within that part of the ancient territory of Louisiana which lay outside of the State of Missouri, and north of the parallel of 36° 3′ of north latitude – a law which, with the exception of one other, was the only statute of freedom then remaining in the Federal code.

In 1856, when the people of Kansas had organized a new State within the region thus abandoned to slavery, and applied to be admitted as a free State into the Union, the Democratic party contemptuously rejected their petition, and drove them with menaces and intimidations from the halls of Congress, and armed the President with military power to enforce their submission to a slave code, established over them by fraud and usurpation. At every subsequent stage of a long contest, which has since raged in Kansas, the Democratic party has lent its sympathies, its aid, and all the powers of the government which it controlled, to enforce slavery upon that unwilling and injured people. And now, even at this day, while it mocks us with the assurance that Kansas is free, the Democratic party keeps the State excluded from her just and proper place in the Union, under the hope that she may .be dragooned into the acceptance of slavery.

The Democratic party, finally, has procured from a supreme judiciary, fixed in its interest, a decree that slavery exists by force of the constitution in every territory of the United States, paramount to all legislative authority, either within the territory or residing in Congress.

Such is the Democratic Party. It has no policy, state or federal, for finance, or trade, or manufacture, or commerce, or education, or internal improvements, or for the protection or even the security of civil or religious liberty. It is positive and uncompromising in the interest of slavery-negative, compromising, and vacillating, in regard to everything else. It boasts its love of equality, and wastes its strength, and even its life, in fortifying the only aristocracy known in the land. It professes fraternity, and, so often as slavery requires, allies itself with proscription. It magnifies itself for conquests in foreign lands, but it sends the national eagle forth always with chains, and not the olive branch, in his fangs.

This dark record shows you, fellow-citizens, what I was unwilling to announce at an earlier stage of this argument, that of the whole nefarious schedule of slave-holding designs which I have submitted to you, the Democratic party has left only one yet to be consummated – the abrogation of the law which forbids the African slave-trade.

~ Postlogue ~

~ Postlogue ~

Senator Seward continued for the next two years to battle for the abolition of slavery, but he cast his ambitions a little too high. In the Republican Convention of 1860, he was an outstanding candidate for the Presidential nomination, and probably would have won it but for the emergence into national prominence of the new figure of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was nominated. Seward lost.

When Lincoln became President, he named Seward as Secretary of State, and Seward’s conduct of that office became his highest distinction. The friendship between Lincoln and Seward, developed during the Civil War, was intimate and exceptionally close.