Hail, Caesar: We who are about to die salute you

~ Prologue ~

~ Prologue ~

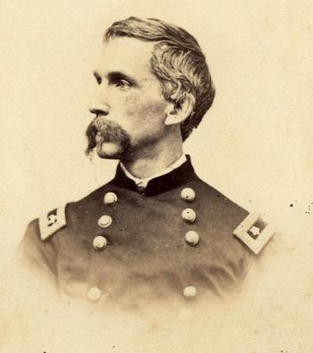

Professor Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain from Bowden College in Maine was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment in 1862 and fought at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Chamberlain believed the Union needed to be supported against the Confederacy by all those willing. On several occasions, Chamberlain spoke freely of his beliefs during his class, urging students to follow their hearts in regards to the war while maintaining that the cause was just. Of his desire to serve in the War, he wrote to Maine’s Governor Israel Washburn, Jr., “I fear, this war, so costly of blood and treasure, will not cease until men of the North are willing to leave good positions, and sacrifice the dearest personal interests, to rescue our country from desolation, and defend the national existence against treachery.”

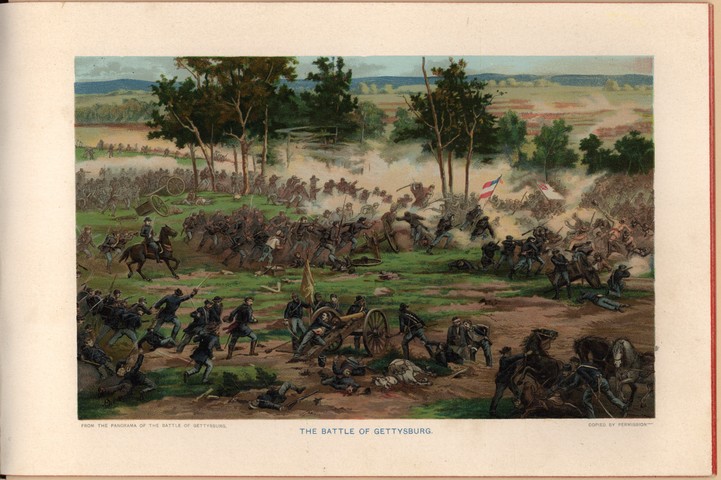

He became commander of his regiment in June 1863. On July 2, during the Battle of Gettysburg, Chamberlain’s regiment occupied the extreme left of the Union lines at Little Round Top. Chamberlain’s men withstood repeated assaults from the 15th Regiment Alabama Infantry and finally drove the Confederates away with a downhill bayonet charge. It has been purported that on this date and just prior to engaging in battle at Gettysburg, he gave the following “speech” to his troops.

In the Roman civil war, Julius Caesar knew he had to march on Rome itself, which no legion was permitted to do. Marcus Lucanus left us a chronicle of what happened:

“How swiftly Caesar had surmounted the icy Alps and in his mind conceived immense upheavals, coming war. When he reached the water of the Little Rubicon, clearly to the leader through the murky night appeared a mighty image of his country in distress, grief in her face, her white hair streaming from her tower-crowned head, with tresses torn and shoulders bare she stood before him, and sighing said:

‘Where further do you march? Where do you take my standards, warriors? If lawfully you come, if as citizens, this far only is allowed.’

Then trembling struck the leader’s limbs; his hair grew stiff and weakness checked his progress, holding his feet at the river’s edge. At last he speaks:

‘O Thunderer, surveying great Rome’s walls from the Tarpeian Rock

‘O Phrygian house gods of Iulus, clan and mysteries of Quirinus who was carried off to heaven

‘O Jupiter of Latium, seated in lofty Alba and hearths of Vesta

‘O Rome, equal to the highest deity, favor my plans.

Not with impious weapons do I pursue you. Here am I, Caesar, conqueror of land and sea, your own soldier, everywhere, now, too, if I am permitted. The man who makes me your enemy – it is he who be the guilty one.’

Then he broke the barriers of war and through the swollen river swiftly took his standards. And Caesar crossed the flood and reached the opposite bank. From Hesperia’s forbidden fields he took his stand and said:

‘Here I abandon peace and desecrated law.

Fortune, it is you I follow.

Farewell to treaties.

From now on war is our judge.'”

Hail, Caesar: We who are about to die salute you.

~ Postlogue ~

Did Lt. Colonel Lawrence actually speak those words to his men? It may be speculative at best, but given that he was an educator and well read on his own accord, it is highly likely that he may have done so.

On the morning of April 9, 1865, Chamberlain learned of the desire by General Robert E. Lee to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia when a Confederate staff officer approached him under a flag of truce. “Sir,” he reported to Chamberlain, “I am from General Gordon. General Lee desires a cessation of hostilities until he can hear from General Grant as to the proposed surrender.” The next day, Chamberlain was summoned to Union headquarters where Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin informed him that he had been selected to preside over the parade of the Confederate infantry as part of their formal surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 12.

Thus Chamberlain was responsible for one of the most poignant scenes of the American Civil War. As the Confederate soldiers marched down the road to surrender their arms and colors, Chamberlain, on his own initiative, ordered his men to come to attention and “carry arms” as a show of respect. In memoirs written forty years after the event, Chamberlain described what happened next:

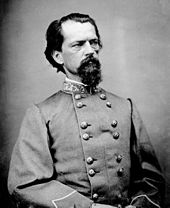

Gen. John B. Gordon

Gordon, at the head of the marching column, outdoes us in courtesy. He was riding with downcast eyes and more than pensive look; but at this clatter of arms he raises his eyes and instantly catching the significance, wheels his horse with that superb grace of which he is master, drops the point of his sword to his stirrup, gives a command, at which the great Confederate ensign following him is dipped and his decimated brigades, as they reach our right, respond to the ‘carry.’ All the while on our part not a sound of trumpet or drum, not a cheer, nor a word nor motion of man, but awful stillness as if it were the passing of the dead.

Chamberlain died of his lingering wartime wounds in 1914 in Portland, Maine, at the age of eighty-five. He is interred at Pine Grove Cemetery in Brunswick, Maine. (Postlogue SOURCE)