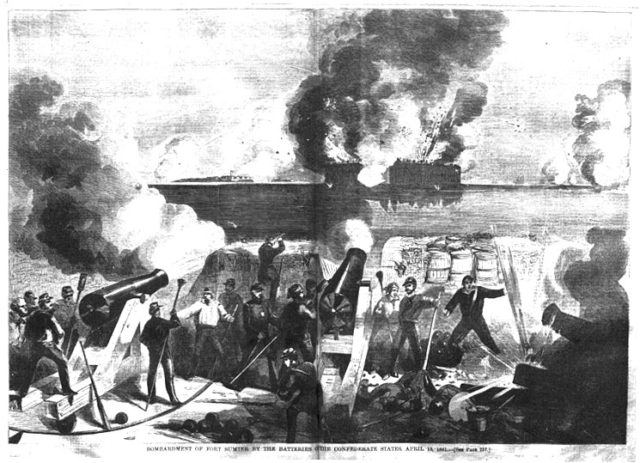

Bombardment of Fort Sumter

At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861, a signal shell fired from a Confederate mortar burst in the sky over the federally occupied island fortress of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Fifteen minutes later, at 4:45, the Confederate batteries around the harbor opened fire on the fort, with the intention of driving out the eighty-five Union troops garrisoned there. The first battle of Fort Sumter, the first battle in the War of Northern Aggression, a war which was, before its end four years later, to claim the lives of approximately three-quarters of a million Americans, soldiers, civilians, and slaves, men, women, and children, and become the bloodiest conflict in the history of this nation, had begun.

History is written, it has been said, by the victors, and history says that this war was fought to end the abhorrent institution of slavery in America. But, as history is indeed written by the victors, it does not always tell the truth of matters involving the armed conflicts of men, and such is the case of what history would come to call the “American Civil War.” History, the history as written by the victors in this war, would have us believe that they were fighting for a noble cause, as indeed the abolition of slavery was, against what they would have us believe was an enemy, made up of former member states of the Union, that was fighting for the ignoble cause of the perpetuation of slavery in America. The truth of the matter is that this war, like so many others, was about money and power. The Northern States, what remained of the United States of America, waged war on the Southern States, which had become the Confederate States of America, in order to subjugate them and forcefully bring them back into the Union, for money and power. The Southern States had seceded peacefully from the Union, their primary motivation being thirty-plus years of unfair taxation, taxation that threatened them with poverty, while enriching the Northern States at their expense.

It started in 1824. Before 1816, the average tariff in the United States had been between fifteen and twenty percent, and had been adequate to meet the needs of the Federal government without putting an excessive burden on any one part of the nation. In 1816, the average tariff in the United States was increased to a full twenty percent, purportedly to help pay for the war of 1812. However, it gave Northern manufacturers a twenty-six percent increase in net profits. At the time, the tariff was not a problem, because it didn’t really put an extra burden on any section of the country. But by 1824, the Northern States, which were dominated by industry and manufacturing, led by Kentucky Representative and Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, began pushing for higher, “protective” tariffs on imports from other countries, which would allow the American manufacturers to sell their goods at higher prices because of less competition from abroad.

The predominately agricultural Southern States emphatically opposed these new protective tariffs, as they raised the cost of manufactured goods purchased not only from abroad, which were often of better quality that those manufactured in the Northern States, but also on those purchased from the North itself. It also meant that foreign countries, whose sales in the United States were reduced due to the higher cost, would not have as much to spend on Southern exports such as cotton and tobacco, of which the larger portion was sold in Europe. Regardless of the damage that could be done to the Southern economy, Congress passed a new protective tariff in 1824, known as the “Sectional Tariff,” that increased the average import duty to between thirty and thirty-five percent, and broadened the range of manufactured goods covered by the tariff. As expected, this caused economic prosperity in the North, and economic privation in the South; South Carolina alone saw a twenty-five percent drop in exports over the next two years.

Southern economic reservations about the protective tariffs were perhaps best illustrated by the “forty bales theory,” which went something like this: A forty percent tariff on cotton finished goods led to forty percent higher consumer prices, which in turn led to forty percent fewer sales, and forty percent fewer sales meant cotton textile manufacturers purchased forty percent less cotton, which meant forty percent less income for cotton growers.

In 1828, matters got worse. Because of higher populations in the Northern States, Congress was dominated by Representatives from the North. In a shameless display of partisanship and greed, this “Northern” Congress passed a new tariff, the goal of which was to protect the fledgling cloth manufacturing industry of New England. This new, more severe tariff would become known as the “Tariff of Abominations.” The Tariff of Abominations imposed even higher duties on manufactured goods imported from Europe, increasing the tax rate to about fifty percent of the value of those goods. While this resulted in substantially greater security for New England cloth manufacturers, it did nothing to benefit the South; in fact, it threatened to devastate the South’s economy. It made manufactured goods purchased from Europe even more expensive, endangering the flow of goods from Great Britain to the South, which in turn threatened the flow of cotton and tobacco to England, because, once again, the loss of revenue would make it more difficult for the British to pay for those commodities. It also made manufactured goods from the Northern States even more expensive, because Northern manufacturers could charge more for their goods and still sell them at a lower price than those from abroad. Hence, the South was losing money because they could not sell as large a portion of their products, and they had to pay higher prices for the manufactured goods that were needed. The Southern States also had no choice but to purchase manufactured goods from the North, which were often of lesser quality than those purchased from abroad, because of the shortage of imports.

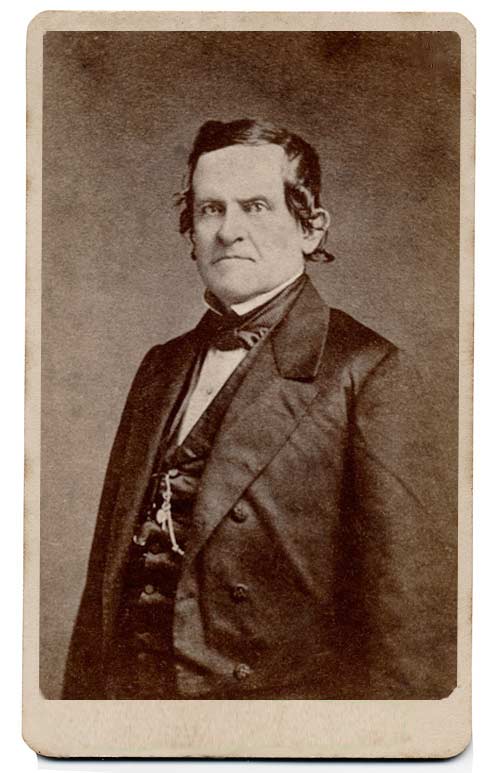

John C. Calhoun

Vice-President John C. Calhoun contended that the legislature of his home state of South Carolina had the right, as a sovereign state, to nullify the tariff for its own economic well-being. South Carolina, which was dependent on its agricultural mass production, or plantation economy, was suffering due to a decline in cotton prices, and was exceptionally adversely affected by the tariff. In April, 1830, Calhoun said, “The Union, next to our liberty, [is] most dear. May we always remember that it can only be preserved by distributing equally the benefits and burdens of the Union.” Words of prophecy? Perhaps.

While the South struggled economically, political friction over the 1828 Tariff of Abominations continued until July of 1832, when Congress passed legislation on a new tariff that lowered duties on some imported manufactured goods, but not on manufactured cloth and iron. The taxes on these items remained at the extremely high rate placed on them in 1828. In spite of years of strong Southern opposition to the obscenely high duties levied on imported manufactured goods, the Tariff of 1832 did nothing to relieve the economic hardships of the South. So, in November of 1832, South Carolina’s special Nullification Convention passed an Ordinance of Nullification that declared both the Tariff of 1828 and the Tariff of 1832 unconstitutional, proclaiming that the tariffs were unenforceable and forbidding the collection of Federal customs duties within the state, defying Federal law. The resulting constitutional crisis, known as the “Nullification Crisis of 1832,” very nearly provoked armed conflict.

President Andrew Jackson

President Andrew Jackson wasted no time in persuading Congress to pass the “Force Act,” which authorized the President to use force of arms to collect Customs duties. Jackson then sent eight United States Navy ships and five thousand troops to Charleston, South Carolina. In the meantime, South Carolina called up the State Militia and began building its forces. President Jackson, enraged by the contempt of his authority, threatened the leaders of the Nullification Movement with hanging. Just when it appeared that war between South Carolina and the United States was imminent, former Vice-President John C. Calhoun and United States Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, working together, calmed the situation in Congress and had yet another tariff drafted. The Tariff of 1833, the “Compromise Tariff,” initiated automatic tax reductions from 1833 to 1842, reducing the tariff back down to approximately fifteen percent, where it stayed until 1860. With the Nullification Crisis over and military conflict averted, President Jackson recalled his forces. This confrontation should have been a lesson to the nation; a lesson in economics, sensitivity to regional needs and production, and plain old political fairness. But, sadly, if it was learned, it would ignored by the ambitious politicians, business factions, and personalities that would enter the political theater in the late 1850’s.

The Northern States purchased approximately twenty percent of the South’s agricultural products in the 1850’s. The vast majority of the South’s agricultural products were exported to Europe, and accounted for seventy-two to eighty-two percent of the United States’ total exports in that decade. However, the South was overwhelmingly dependent on European and Northern manufactured goods, needed for both consumer needs and use in agricultural production. As had been the case before, a protective tariff at that time would have an enormous benefit to the manufacturing and industrial states of the North, but would have been economically devastating to the South. The old Whig Party, which had always pressed for high protective tariffs, had ceased to exist by 1855. The new Republican Party replaced the Whig Party, and adopted the latter’s policy of promoting the high protective tariffs that enriched the Northern States while impoverishing the Southern States. In 1857, a recession struck the country, giving the politics of protectionism a considerable boost in the industrial North.

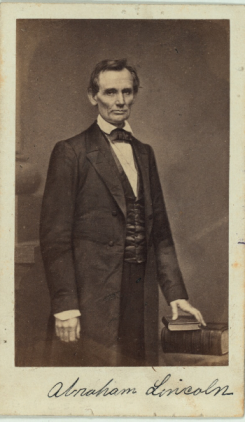

In 1860, tariffs on imported manufactured goods were responsible for approximately ninety-five percent of the United States’ government’s revenue. In that year’s Presidential election, Republican candidate, admirer of the late Henry Clay, and former Whig, Abraham Lincoln, campaigned for the Morrill Tariff, which was part of the Republican Party Platform. The tariff would raise the average tax on imported manufactured goods from approximately fifteen percent to thirty-seven percent immediately, to be increased to forty-seven percent within three years. This was nearly identical to the 1828 Tariff of Abominations which had caused the constitutional crisis of 1832 and nearly led to the secession of South Carolina and the use of armed force by the United States government against South Carolina. In spite of this, on May 10, 1860, the House of Representatives, thirty-sixth United States Congress, December 5, 1859 – March 27, 1861, voted on the Morrill Tariff, House Resolution 338, and passed it with a vote of one hundred and five to sixty-four. The recorded votes of the House are as follows:

Recorded House of Representatives votes on H.R. 338, May 10, 1860

112 delegates from Union States

97 “yea” 15 “nay”

17 delegates from Border States

7 “yea” 10 “nay”

40 delegates from Southern States

1 “yea” 39 “nay”

169 total delegates

105 “yea” 64 “nay”

As can be seen, even had the one Southern and seven Border delegates that voted in favor of the tariff had voted against it, there was never a chance that it would not pass.

Henry C. Carey

Sometime in mid-1860, Henry C. Carey, Lincoln’s economic “guru” and future chief economic adviser made a prophetic statement in a letter to the author of the Morrill Tariff, United States Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont, when he wrote that, “Nothing less than a dictator is required for making a really good tariff.” On September 27 of 1860, Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, an iron manufacturer, rabid abolitionist, and the most politically powerful Republican in Congress, who was also a co-sponsor of the Morrill Tariff, during a speech in New York City, said that of the two most important issues of the Presidential campaign, preventing the expansion of slavery into new states and passing the Morrill Tariff, the new tariff was the most important. He said that the tariff would bring great prosperity to the Northeast, and would impoverish the South, along with the western states. It was, he told the crowd, essential to the advancement of national greatness and to bringing prosperity to the industrial workers of the North. He also said that if Southern leaders objected to the tariff, that they would be rounded up and hanged.

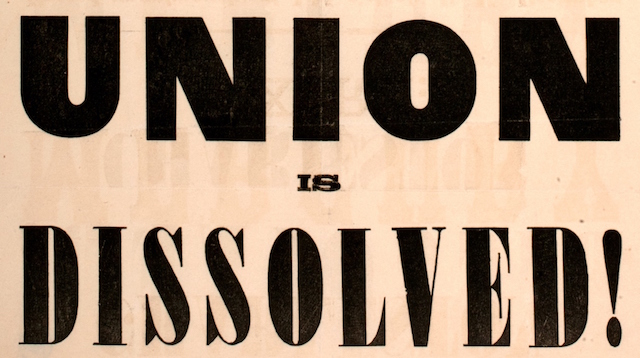

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected as the sixteenth President of the United States. With Lincoln winning the election and Northern dominance of Congress bolstered, leaders in South Carolina and the Gulf States began the call for secession. Southern newspapers began to condemn the actions of Congress concerning the Morrill Tariff. An editorial in the November 4, 1860 edition of the Charleston Mercury said of the tariff crisis: “The real causes of dissatisfaction in the South with the North, are in the unjust taxation and expenditure of the taxes by the Government of the United States, and in the revolution the North has effected in this government, from a confederated republic, to a national sectional despotism.” Some Northern newspapers even condoned secession should the Southern States adopt that course of action. In the November 21, 1860 edition of the Cincinnati Daily Press, an editorial said of secession: “We believe that the right of any member of this Confederacy to dissolve its political relations with the others and assume an independent position is absolute.”

On 20 December, 1860, that very thing happened, when South Carolina officially seceded from the Union. Mississippi followed suit on January 9, 1861. On the same day that an attempt was made by the USS Star of the West to resupply and reinforce the Federal troops garrisoned at Fort Sumter with 200 men and was repulsed by South Carolina harbor defenses. Florida seceded the next day, and Alabama was next, seceding on January 11th. On 19 January, Georgia seceded, and Louisiana followed, seceding on the 26th. On February 1, 1861, Texas became the seventh state to secede from the Union.

What happened next was to be expected, as the secessionist states now considered themselves free of Union control. During the month of February, 1861, Federal forts, and the munitions kept there, in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas are peacefully taken and occupied by state militias. On 4 February, delegates from South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas convened in Montgomery, Alabama, to establish the Confederate States of America. They did so over the next five days, electing Jefferson Finis Davis of Mississippi as Provisional President of the Confederate States of America on 9 February. On that very day, a second resupply vessel, bound for Fort Sumter, was repulsed by Confederate batteries. On February 13, 1861, the Virginia Secession Convention convened in Richmond.

What happened next was to be expected, as the secessionist states now considered themselves free of Union control. During the month of February, 1861, Federal forts, and the munitions kept there, in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas are peacefully taken and occupied by state militias. On 4 February, delegates from South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas convened in Montgomery, Alabama, to establish the Confederate States of America. They did so over the next five days, electing Jefferson Finis Davis of Mississippi as Provisional President of the Confederate States of America on 9 February. On that very day, a second resupply vessel, bound for Fort Sumter, was repulsed by Confederate batteries. On February 13, 1861, the Virginia Secession Convention convened in Richmond.

RELATED: The Morrill Tariff as published in The New York Times, February 14, 1861

On February 20, 1861, the United States Senate, thirty-sixth United States Congress, December 5, 1859 – 27 March, 1861, voted on H.R. 338, the Morrill Tariff, and passed it with a vote of twenty-five to fourteen. The recorded votes of the Senate are as follows:

Recorded Senate votes on H.R. 338, February 20, 1861

29 delegates from Union States

25 “yea” 4 “nay”

3 delegates from Border States

0 “yea” 3 “nay”

7 delegates from Southern States

0 “yea” 7 “nay”

39 total delegates

25 “yea” 14 “nay”

Again, there was never a chance that it would not pass. The Senate made its final amendments to the Morrill Tariff on March 2, 1861, and sent the bill to President James Buchanan who signed it into law that very day.

Justin S. Morrill

Before the Morrill Tariff was even introduced, tariff duties collected from the South already accounted for eighty-seven percent of the total United States tariff revenues. The Morrill Tariff increased that percentage, and again, while protecting Northern industrial and manufacturing interests, it caused the cost of living and commerce in the South to skyrocket, and also, once again, caused a significant drop in the trade value of Southern agricultural exports to Europe. This caused a prevalence of severe economic hardship and poverty in the South. Perhaps the worst part of it all was the fact that eighty percent or more of the revenues collected through the Morrill Tariff were spent on Northern public works and subsidizing Northern industry and manufacturing, enriching the North even more at the expense of the South.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the sixteenth President of the United States. In his inaugural speech, Lincoln endorsed the Morrill Tariff and promised to enforce it, even in the seceded states, and that he would use force to do so if necessary. On 11 March, 1861, the Congress of the Confederate States of America adopted its own Constitution. At this point, manufacturers and industrialists in the North started to become anxious when they realized that the North, dependent on tariff revenue, would be in competition with a “free-trade” South. It was not only the loss of tax revenues that they feared, but significant loss of trade to Europe. Editorials in Northern newspapers began to not only reflect this nervousness, but also the growing sentiment of leaving the seceded states alone. An editorial in the March 21, 1861 edition of the New York Times said of secession: “There is a growing sentiment throughout the North in favor of letting the Gulf States go.” But Lincoln couldn’t bring himself to let the revenues to be gained by the Morrill Tariff go uncollected. Because of this, his actions in early April would cause the nation to become embroiled in a cataclysmic war. On April 4, 1861, when he was asked by John Baldwin (attorney, Unionist, and future Confederate soldier and Congressman) if he would use force to return the South to the Union, he had answered, “Am I to let them go, and open Charleston [and other Southern ports] as ports of entry with their ten percent tariff? What then would become of my tariff?” On that same day, Lincoln ordered ships carrying supplies, munitions, and two hundred soldiers to Fort Sumter to resupply and reinforce the eighty-five Federal soldiers garrisoned there.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the sixteenth President of the United States. In his inaugural speech, Lincoln endorsed the Morrill Tariff and promised to enforce it, even in the seceded states, and that he would use force to do so if necessary. On 11 March, 1861, the Congress of the Confederate States of America adopted its own Constitution. At this point, manufacturers and industrialists in the North started to become anxious when they realized that the North, dependent on tariff revenue, would be in competition with a “free-trade” South. It was not only the loss of tax revenues that they feared, but significant loss of trade to Europe. Editorials in Northern newspapers began to not only reflect this nervousness, but also the growing sentiment of leaving the seceded states alone. An editorial in the March 21, 1861 edition of the New York Times said of secession: “There is a growing sentiment throughout the North in favor of letting the Gulf States go.” But Lincoln couldn’t bring himself to let the revenues to be gained by the Morrill Tariff go uncollected. Because of this, his actions in early April would cause the nation to become embroiled in a cataclysmic war. On April 4, 1861, when he was asked by John Baldwin (attorney, Unionist, and future Confederate soldier and Congressman) if he would use force to return the South to the Union, he had answered, “Am I to let them go, and open Charleston [and other Southern ports] as ports of entry with their ten percent tariff? What then would become of my tariff?” On that same day, Lincoln ordered ships carrying supplies, munitions, and two hundred soldiers to Fort Sumter to resupply and reinforce the eighty-five Federal soldiers garrisoned there.

Governor Francis Pickens

On April 6, 1861, Lincoln formally informed Governor Francis Pickens of South Carolina that he intended to resupply the troops at Fort Sumter, whose garrison was to be tasked with collecting the duties levied by the Morrill Tariff, with provisions only, and assured Governor Pickens that the resupply vessels would be unarmed. Governor Pickens ordered that the supplies not to be allowed to land. On April 11, Major Robert Anderson, commander of the Union forces at Fort Sumter, refused to surrender the fort after having repeatedly refused previous calls to abandon it. That afternoon, the USS Harriet Lane, a Federal gunboat, and the first of the “resupply” ships arrived at Charleston harbor. That evening, she fired a warning shot across the bow of the USS Nashville, having mistaken the Nashville for a Confederate vessel as she sailed past Charleston harbor with no colors hoisted. This proved that Lincoln had lied about the resupply ships being unarmed. At 3:00 in the morning on April 12, 1861, the USS Baltic, the second of the resupply ships reached Charleston Harbor. At 3:45 that morning Major Anderson was given an ultimatum; abandon Fort Sumter, or be fired upon. Once again, he refused. He was then informed that the Confederates batteries would open fire at 4:30 a.m. As promised, at 4:30 a.m. the shell that signaled the beginning of the war burst in the sky above Fort Sumter.

The passage and promised enforcement of the Morrill Tariff made it clear that the Union was concerned only with Northern interests and that the South was nothing more to the United States government than a tool to be used in promoting those Northern interests, and the whole world knew it. In October of 1861, Karl Marx, who favored the North like most European socialists of the time, said in an article published in England, that, “The war between the North and South is a tariff war. The war, is further, not for any principle, does not touch the question of slavery, and in fact turns on the Northern lust for power.” In December of that year, Charles Dickens, famous English author and a strong opponent of slavery, said about the War of Northern Aggression: “… the Northern onslaught upon slavery is no more than a piece of specious humbug disguised to conceal its desire for economic control of the United States… Union means so many millions a year lost to the South; secession means loss of the same millions to the North. The love of money is the root of this as many, many other evils. The quarrel between the North and South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel.”

None could have said it better.

RELATED: Lincoln’s Tariff War

September 20, 2017

K. Lance Spivey

Deo Vindice

Pingback: This Country Has A Big Problem – Public Schools! | Metropolis.Café

Pingback: Part Two ~ This Country Has A Big Problem – Public Schools! | Metropolis.Café

Pingback: Slavery ~ the Issue That Wasn’t THE Issue | Metropolis.Café