Washington privately expressed his growing disdain for the institution – and his desire for its eventual abolition

December 21, 1772 ~ Ferry Farm, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, on the banks or the Rappahannock River, was one of several properties owned by George Washington’s father, Augustine. He acquired the property in 1738 and moved his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, to the farm along with their five young children. Augustine died suddenly in 1743 at age 49. He left his Mount Vernon estate to Lawrence, his eldest son from his first marriage, and Ferry Farm, with its ten slaves, to George, who was 11 years old at the time. Mary retained control of the farm until he came of age at 21.

December 21, 1772 ~ Ferry Farm, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, on the banks or the Rappahannock River, was one of several properties owned by George Washington’s father, Augustine. He acquired the property in 1738 and moved his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, to the farm along with their five young children. Augustine died suddenly in 1743 at age 49. He left his Mount Vernon estate to Lawrence, his eldest son from his first marriage, and Ferry Farm, with its ten slaves, to George, who was 11 years old at the time. Mary retained control of the farm until he came of age at 21.

The farm was Washington’s boyhood home from the time he was 6 until age 13, when Mary allowed him to go to Mount Vernon and live with his half-brother Lawrence. Through Lawrence’s efforts, George received an appointment as midshipman in the Royal Navy, but Mary refused to allow him to accept. With the exception of his time at Lawrence’s estate, most of the events in Washington’s early life took place at Ferry Farm. After his father’s death, his chances for formal education in England dimmed. Instead, he set onto a course of self-study to become a proper Virginia gentleman, copying The Rules of Civility, an etiquette manual, and learning fencing, dancing, and equestrian skills. During his time at Ferry Farm, he also trained as a surveyor, and in 1748, at age 16, he accompanied Lord Fairfax on a surveying expedition to the western Virginia hinterlands. Although now known to be a quaint myth, the apocryphal tale of Washington and the cherry tree would have taken place at Ferry Farm. In 1753, Washington began his military career, which brought an end to his childhood at the farm.

After George became the legal owner of Ferry Farm, Mary was financially obliged to her son. She continued farming there, using slaves as her labor force. When Washington inherited his half-brother’s Mount Vernon plantation, some 40 miles north, in 1761, he turned his attention to the new estate. In the fall of 1771, Washington conducted a survey of Ferry Farm, evidently in anticipation of leasing the property. At the same time, his brother Charles and brother-in-law Fielding Lewis prepared an inventory of the farm holdings. The next year, Washington moved his aging mother to a house he had purchased for her in the town of Fredericksburg. He then leased the farm to neighbors until finding a buyer for the property in 1774. (The new owner, Dr. Hugh Mercer, became a brigadier general in the Continental Army. He was killed in the Battle of Princeton.)

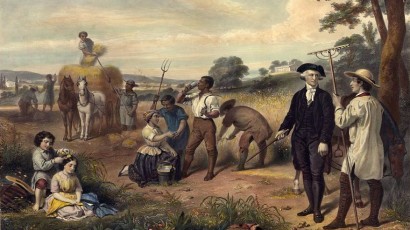

Washington as Farmer at Mount Vernon, by Junius Brutus Stearns, 1851. Number 50.2.4, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Four enslaved individuals are cited by name in this letter: Giles (Washington’s driver), Silla, Toney, and Patt. A February 1786 inventory of his slaveholdings shows that Washington owned 216 men, women and children (105 were owned outright; the remaining 111 were “dower slaves” from the estate of Martha Washington’s first husband). Over the course of his life, Washington privately expressed his growing disdain for the institution – and his desire for its eventual abolition, but never publicly spoke out against it. As scholar Dorothy Twohig points out, it’s not clear whether Washington’s disgust at slavery rested “on moral grounds (although there are some indications that this is so) or primarily on the grounds of the institution’s economic inefficiencies.” Washington’s refusal to break up slave families and his insistence on their humane treatment support the former premise. His voiced objections to the sheer inefficiency of slave labor suggest that the latter consideration weighed in as well. In his July 1799 will, Washington manumitted all of the slaves held in his own name after he and Martha died.

Charles Washington (1738-1799), the youngest brother of George Washington, was a prominent local landholder and the founder of Charles Town, the current seat of Jefferson County, West Virginia. Like George, Charles had grown up on Ferry Farm. His eldest son, George Augustine, would later marry Martha Washington’s niece, Frances “Fanny” Bassett, and serve as his uncle’s estate manager at Mount Vernon.

Mount Vernon Decr. 21st . 1772

Dear Brother,

Your Letter of the 17th by Giles never reach’d my hands till yesterday after noon, in answer to it I must get the favour of you to dispose of the Porke for me, taking an Acct. of what my Mother has. The smallest and most indifferent of the Hogs, may be set a part for the overseer’s share. What Hogs will still remain please to order Powell to sell, only reserving a Sow or two to be supported upon the shatter’d Corn [to] raise his Provisions against another year in case it should be w[a]nted. Be pleased also to let a pair of the Oxen from Jones’s, be added to those, which Powell now has, & kept there for the use of his Plantation. Let Powell also keep 3 or 4 Cows to supply himself & the Negro’s with Milk; and also keep a Bull with them; after which, please to order Ned Jones to set of[f] with all the remaining Cattle, the Sheep, and Oxen, for this place. He is to bring the two young Fellows, & the Wench Silla up with him, and as they may have some of their Cloaths and other things to bring, he might bring the Cart along with him provided there is Oxen enough to draw it after. Powell has got two of them away. He must be very carefull not to overload the Cart & I hope will be as carefull not to loose any of the stock by the way by over driving of them. Whatever expence he is at upon the Road for the stock I will pay. The Negroes may bring their own provisions along with them. The Wench Patt is to go down to Powells; so is Toney, but he should stay at the upper place to take care of the Houses & Plantation till Colo. Lewis Rents or does something with it which please to tell him I hope he will do soon. I should be much obliged to you also for disposing of what Corn there is to spare (if any) and the Fodder before either of them are wasted or destroy’d. I am sorry to give you so much trouble, but I am under some kind of necessity; and hope I shall not long have occasion to give you much more being with Love in which Mrs. Washington joins to your self my Sisters Mother &c

Yr most Affecte. Brother

Geo. Washington

PS. If Jones should have taken his departure, & can not be [got to come] up with the People or stock, pray write me word by the next Post, that I may send a Person down from hence for them. If Powell should dye, also write me word of it immediately, and when ever my Mother will consent that those [hands] should be moved up now as I had rather do this [3] than look out for another overseer at that place [Ferry Farm] where I am sure of sinking Money every year that I attempt to work it. The Plantation may, I suppose, be Rente; or I could keep it inclos’d for the sake of the Wheat that is sow’d altho no Negro’s should remain thereon.