“The older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment of others.”

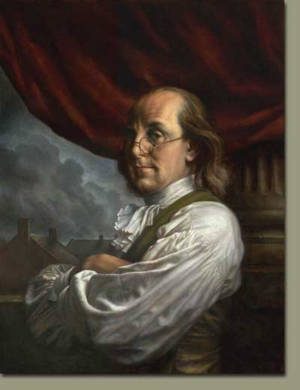

Dr. Benjamin Franklin

PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania, 1787 – In a speech on the newly written Constitution, before the Convention here at which he is the eldest sage among sages, 8I – year-old Benjamin Franklin did much toward assuring adoption of this notable document by his injection of homely philosophy into the oft-times heated debate.

The diplomatic editor of Poor Richard’s Almanack frankly told his colleagues that he is not satisfied with the Constitution drafted for submission to the States, and yet he expressed doubt that he ever would be satisfied.

More than that, however, he counseled his fellow members of the Convention against such a predisposition toward personal feelings about it as to break the unanimity of support that it must have among its authors.

The Constitution, he emphasized, represents a compromise among many ideas . . . compromise and agreement among prejudices, passions, local interest and selfishness of views.

I confess that I do not entirely approve of this Constitution at present; but, sir, I am not sure I shall never approve of it, for, having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that, the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment of others. Most men, indeed, as well as most sects in religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them, it is so far error. Steele, a Protestant, in a dedication, tells the pope that the only difference between our two churches in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrine is, the Romish Church is infallible, and the Church of England is never in the wrong. But, though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who, in a little dispute with her sister, said: “But I meet with nobody but myself that is always in the right.”

In these sentiments, sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults – if they are such – because I think a general government necessary for us, and there is no form of government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered; and I believe, further, that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other. I doubt, too, whether any other convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution; for, when you assemble a number of men, to have the ad- vantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?

It therefore astonishes me, sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our counsels are confounded.