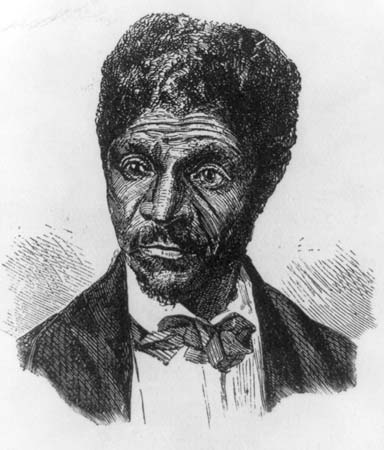

Dred Scott

From the 1780s, the question of whether slavery would be permitted in new territories had threatened the Union. Over the decades, many compromises had been made to avoid disunion. But what did the Constitution say on this subject? This question was raised in 1857 before the Supreme Court in case of Dred Scott vs. Sandford. Dred Scott was a slave of an army surgeon, John Emerson. Scott had been taken from Missouri to posts in Illinois and what is now Minnesota for several years in the 1830s, before returning to Missouri. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had declared the area including Minnesota free. In 1846, Scott sued for his freedom on the grounds that he had lived in a free state and a free territory for a prolonged period of time. Finally, after eleven years, his case reached the Supreme Court. At stake were answers to critical questions, including slavery in the territories and citizenship of African-Americans. The verdict was a bombshell.

* The Court ruled that Scott’s “sojourn” of two years to Illinois and the Northwest Territory did not make him free once he returned to Missouri.

* The Court further ruled that as a black man Scott was excluded from United States citizenship and could not, therefore, bring suit. According to the opinion of the Court, African-Americans had not been part of the “SOVEREIGN PEOPLE” who made the Constitution.

* The Court also ruled that Congress never had the right to prohibit slavery in any territory. Any ban on slavery was a violation of the Fifth Amendment, which prohibited denying property rights without due process of law.

* The Missouri Compromise was therefore unconstitutional.

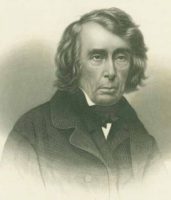

The Chief Justice of the United States was Roger B. Taney, a former slave owner, as were four other southern justices on the Court. The two dissenting justices of the nine-member Court were the only Republicans. The north refused to accept a decision by a Court they felt was dominated by “Southern fire-eaters.” Many Northerners, including Abraham Lincoln, felt that the next step would be for the Supreme Court to decide that no state could exclude slavery under the Constitution, regardless of their wishes or their laws.

Two of the three branches of government, the Congress and the President, had failed to resolve the issue. Now the Supreme Court rendered a decision that was only accepted in the southern half of the country. Was the American experiment collapsing? The only remaining national political institution with both northern and southern strength was the Democratic Party, and it was now splitting at the seams. The fate of the Union looked hopeless.

Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the United States

~ The Supreme Court’s Decision ~

When the Court met for the first time since the reargument to discuss the case on February 14, 1857, it favored a moderate decision that ruled in favor of Sanford but did not consider the larger issues of Negro citizenship and the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. The majority chose Justice Nelson as the writer of a decision that avoided these important but highly controversial issues, and Nelson went to work on it. When Nelson presented his opinion to the majority, however, he discovered that his “majority” opinion turned out to be the opinion of only himself. The Court elected to throw out Nelson’s decision and instead chose Chief Justice Roger B. Taney as the writer of the true majority opinion for the court, an opinion that would include everything under consideration in the case, including Negro citizenship and the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. According to Justice Catron, one of the members of the majority, “the court majority. . .had been `forced up’ to its change of plan by the determination of [Justices] Curtis and McLean to present extensive dissenting opinions discussing all aspects of the case.” The majority decided that if the dissenters covered all the issues, they must also. Ironically, the two most antislavery justices may have forced a more proslavery opinion than what the majority originally planned to decide.

By mid-February 1857, many well-informed Americans were aware that the conclusion of the Scott v. Sandford case was close at hand. President-elect James Buchanan contacted some of his friends on the Supreme Court starting in early February; he asked if the Court had reached a decision in the case, for he needed to know what he should say about the territorial issue in his inaugural address on March 4. By inauguration day 1857, Buchanan knew what the outcome of the Supreme Court’s decision would be and took the opportunity to throw his support to the Court in his inaugural address:

A difference of opinion has arisen in regard to the point of time when the people of a Territory shall decide this question [of slavery] for themselves.

This is, happily, a matter of but little practical importance. Besides, it is a judicial question, which legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending, and will, it is understood, be speedily and finally settled. To their decision, in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit, whatever this may be.

Just two days after Buchanan’s inauguration, on March 6, 1857, the nine justices filed into the courtroom in the basement of the U.S. Capitol, lead by Chief Justice Taney. Taney was almost 80 years old, always physically feeble, and even weaker as a result of the effort he had put forth to write the two-hour-long opinion; therefore, he spoke in a low voice that Republicans deemed appropriate for such a “shameful decision.” He first addressed the question of Negro citizenship, not only that of slaves but also that of free blacks:

Can a Negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?

One of the privileges reserved for citizens by the Constitution, argued Taney, was the “privilege of suing in a court of the United States in the cases specified by the Constitution.” Taney’s opinion stated that Negroes, even free Negroes, were not citizens of the United States, and that therefore Scott, as a Negro, did not even have the privilege of being able to sue in a federal court. Taney then turned to the question of the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. The territories acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Taney stated, were dependent upon the national government, and the government could not act outside its framework as set forth in the Constitution. Congress, for example, could not deny the citizens of the new territory freedom of speech. Similarly, Congress could not deprive the citizens of the territory of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law,” according to the Fifth Amendment. Taney continued:

And an act of Congress which deprives a citizen of the United States of his liberty or property, merely because he came himself or brought his property into a particular territory of the United States, and who had committed no offense against the laws, could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law.

The Constitution made no distinction between slaves and other types of property. Taney reasoned that the Missouri Compromise deprived slaveholding citizens of their property in the form of slaves and that therefore the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Scott’s case had one last hope: the Chief Justice could decide that Scott was free because of his stay in the free state of Illinois. Taney made no such decision, instead stating that “the status of slaves who had been taken to free States or territories and who had afterwards returned depended on the law of the State where they resided when they brought suit.” Scott had brought suit in Missouri and hence he was still a slave because Missouri was a slave state. Taney ruled that the case be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction and sent back to the lower court with instructions for that court to dismiss the case for the same reason, therefore upholding the Missouri Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of Sanford.