“Liberty is the proper end and object of authority.”

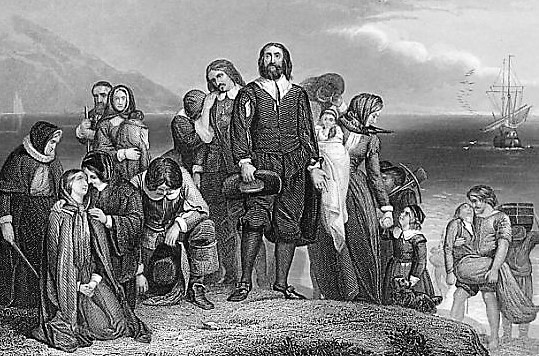

Governor John Winthrop

PLYMOUTH COLONY, 1645 – Governor John Winthrop defined the duty of “magistrates,” or elected governing officials, as that of preserving the liberties of those they govern within all possible limits of human capacities, in a speech concluding a grave court dispute carried to Boston from the town of Hingham.

Simple as the judgment may seem to be, it constitutes a new definition added to the slim archives of precedent being constructed as part of the colonial legal structure. The case began at Hingham when a militia company, or “train-band,” deposed its elected lieutenant. When the lieutenant appealed to Boston for assistance in regaining his position, he won a commendation but the town refused to abide by the senior decision. A group of townsmen carried the case to court by suing Governor Winthrop.

After winning the case, the governor demanded the right to spread upon the record his own views.

The great questions that have troubled the country are about the authority of the magistrates and the liberty of the people. It is yourselves who have called us to this office, and, being called by you, we have our authority from God, in way of an ordinance, such as hath the image of God eminently stamped upon it, the contempt and violation whereof hath been vindicated with examples of divine vengeance. I entreat you to consider that, when you choose magistrates, you take them from among yourselves, men subject to like passions as you are. Therefore when you see infirmities in us, you should reflect upon your own, and that would make you bear the more with us, and not be severe censurers of the failings of your magistrates, when you have continual experience of the like infirmities in yourselves and others. We account him a good servant who breaks not his covenant. The covenant between you and us is the oath you have taken of us, which is to this purpose, that we shall govern you and judge your causes by the rules of God’s laws and our own, according to our best skill. When you agree with a workman to build you a ship or house, etc., he undertakes as well for his skill as for his faithfulness, for it is his profession, and you pay him for both. But when you call one to be a magistrate, he doth not profess nor undertake to have sufficient skill for that office, nor can you furnish him with gifts, etc., therefore you must run the hazard of his skill and ability. But if he fails in faithfulness, which by his oath he is bound unto, that he must answer for. If it fallout that the case be clear to common apprehension, and the rule clear also, if he transgress here, the error is not in the skill, but in the evil of the will: it must be required of him. But if the case be doubtful, or the rule doubtful, to men of such I understanding and parts as your magistrates are, if your magistrates should err here, yourselves must bear it.

For the other point concerning liberty, I observe a great mistake in the country about that. There is a two-fold liberty, natural (I mean as our nature is now corrupt) and civil or federal. The first is common to man with beasts and other creatures. By this, man, as he stands in relation to man simply, hath liberty to do what he lists; it is a liberty to evil as well as to good. This liberty is incompatible and inconsistent with authority, and cannot endure, the least restraint of the most just authority. The exercise and maintaining of this liberty makes men grow more evil, and in time to be worse than brute beasts: omnes sumus licentia deteriores. This is that great enemy of truth and peace, that wild beast, which all the ordinances of God are bent against, to restrain and subdue it.

The other kind of liberty I call civil or federal; it may also be termed moral, in reference to the covenant between God and man, in the moral law, and the politic covenants and constitutions, amongst men themselves. This liberty is the proper end and object of authority, and cannot subsist without it; and it is a liberty to that only which i is good, just, and honest. This liberty you are to stand for, with the hazard (not only of your good, but) of your lives, if need be. Whatsoever crosseth this is not authority, but a distemper thereof. This liberty is maintained, and exercised in a way of subjection to authority; it is of the same kind of liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free. The woman’s own choice makes such a man her husband; yet, being so chosen, he is her lord, and she is to be subject to him, yet in a way of liberty, not of bondage; and a true wife accounts her subjection her honor and freedom, and would not think, her condition safe and free but in her subjection to her husband’s authority. Such is the liberty of the church under the authority of Christ, her king; and husband; his yoke is so easy and sweet to her as a bride’s ornaments; and if through forwardness or wantonness etc. she shake it off, at any time, she is at no rest in her spirit until she take it up again; and whether her lord smiles upon her, and embraceth her in his arms, or whether he frowns, or rebukes, or smites her, she apprehends the sweetness of his love in all, and is refreshed, supported, and instructed by every such dispensation of his authority over her. On the other side, ye know who they are that complain of this yoke and say, let us break their bands etc. we will not have i this man to rule over us. Even so, brethren, it will be between you and I your magistrates. If you stand for your natural corrupt liberties, and will, do what is good in your own eyes, you will not endure the least weight of authority, but will murmur, and oppose, and be always striving to shake off that yoke; but if you will be satisfied to enjoy such civil and lawful liberties, such as Christ allows you, then will you quietly and cheerfully submit unto that authority which is set over you, in all the administrations of it, for your good. Wherein, if we fail at any time, we hope we shall be willing (by God’s assistance) to hearken to good advice from any of you, or in any other way of God; so shall your liberties be preserved, in upholding the honor and power of authority amongst you.

The deputy governor having ended his speech, the court arose, and the magistrates and deputies retired to attend their other affairs.

~ Postlogue ~

Governor Winthrop’s legal victory, more than three centuries ago and his subsequent speech, became important precedents that carried through debates during the next two centuries.

John Winthrop and his followers – the Puritans

In a country founded upon the basis of individual liberty, but yet one faced with the necessity to live within the bounds of legal order, this statement served as a foundation for the development of Republican and Whig arguments against the growth of over-riding central authority vested in individuals.